George Lucas grew up in a small town, Modesto, California, where on Friday nights the guys hopped in their freshly washed and waxed cars and cruised the streets, rock and roll blaring out of the rolled down windows. Everyone knew each other so the streets were alive as though one big party were happening.

George Lucas grew up in a small town, Modesto, California, where on Friday nights the guys hopped in their freshly washed and waxed cars and cruised the streets, rock and roll blaring out of the rolled down windows. Everyone knew each other so the streets were alive as though one big party were happening.

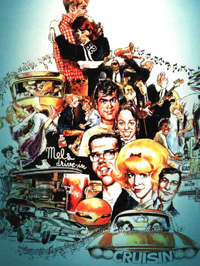

Lucas, with William Huyck and Gloria Katz, would later write the screenplay for “American Graffitti,” a remarkable little film set in 1962 and a small town in California on the last night of summer before school begins. Loosely based on experiences Lucas had as a teenager, the film would become a touchstone for a generation, having an impact on pop culture no one expected. For the generations after the 1970s that have seen the film, it has the same curious effect, and without sounding self-important or condescending, that impact will grow as they, and we, continue to age.

Why? We knew people like this. We were people like this.

The film is familiar for almost anyone who ever went to high school, perhaps more so to small town natives. We all knew the town tough guy who hung around with the high school kids long after he had left school because he needs the adoration they give him. There was the class geek: glasses-wearing, short, trying a little too hard to please, but likable just the same.

The class jock, who would also be the class president dating the head of the cheerleader sqaud, and the intellectual, who could not wait to get out of the town and see what the world held for him. All of us, sometime in our lives at school, knew people like this, perhaps even were people like this.

What allowed Lucas’s film to have such an extraordinary power was the ending (36 years old…it’s exempt from spoiler attacks) when as the plane flies away with Curt (Richard Dreyfuss), we see black and white photographs of the kids and a line or two of what the future holds for them. We’re told John Milner (Paul Le Mat), the tough guy, will be killed by a drunk driver, his worst fear. Terry the Toad (Charles Martin Smith) will end up missing in action in Vietnam, while Steve (Ron Howard), the class president, will marry his sweetheart Laurie (Cindy Williams), only to divorce her a short time later. And the intellectual, Curt, will be a writer living in Canada, perhaps to avoid the draft?

These descriptions made the film bittersweet, because we learn, as we do in life, that the future is not always so bright. Though the film ends with smiles and tears, can any of them see this bleak forecast? Certainly not. Terry is the last guy one would think to end up in Vietnam, while John, we think, is too smart to be killed, yet both meet horrible fates.

Lucas made the film even more familiar to us by giving the characters these trajectories, because how many of the people we remember from high school achieved their dream, were killed, or watched their lives fall apart in one way or another?

I knew a guy in high school, good guy, the school tough guy, and a finer fighter I have never encountered. Good hockey player, not much of a student but was likely going to parlay those hockey skills into a scholarship of some kind. Never happened. He got into drugs, then got into more trouble and ended up working in the local hardware store before his car broke down on a road one night. He hitched a ride with a a guy, and a few minutes later, the two of them were hit head on in a crash that killed them both. Looking at old school pictures, I see the smile on his face and the hope for what he thought was coming that never did. Lucas knew these emotions as well.

“American Graffiti” is about innocence lost, the transition from youth to adult and the leaving of behind a life with few responsibilities into one that is fraught with them. On a grander scale, the film is political, 1962 being the last true year of innocence in America, the year before President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, forever altering the way everyone thought about their country, their government, the world, really.

Francis Ford Coppola produced the film for Lucas, continuing to be the mentor he had been for the younger man in film school, and in a famous incident moments after a screening, he saved the film for Lucas. The executives at Universal were not happy with the film, believing it to be impossible to release. Coppola flew into a fury, screaming at them that Lucas had delivered an excellent film that would not only make money but be a critics’ darling. In a grand showman’s gesture, he whipped out his check book and offered to buy the film from Universal on the spot, an offer they declined, suddenly sensing that if Coppola felt this way, surely the film had merit.

It certainly did.

“American Graffiti” grossed over $60 million in the United States and earned rave reviews from the nation’s critical community. It was later nominated for Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay and Best Supporting Actress (Candy Clark) and would lose to the forgettable ‘The Sting.” Of the films nominated that year, “American Grafitti” was by far the best. And I have always believed Paul Le Mat, Carles Martin Smith and Mackenzie Phillips deserved nominations in their respective supporting categories for splendid performances that remain as good today as they were three decades ago.

A quick glance at the film’s impact on pop culture reveals a soundtrack album that caused a resurgence in the populairity of 60s rock, and at least two television shows that owe their existence to the film: “Happy Days” and later “Laverne & Shirley.” Audiences stung by the isues in the 1970s seemed to long for a simpler time.

This was likely the last time, perhaps the only time, that Lucas actually DIRECTED his actors. The stars of “Star Wars” complained bitterly that they received little direction from the director, under incredible pressure no doubt due to the intense effects work in the film. I believe “American Graffiti” is therefore Lucas’s greatest work to date. This film moved me deeply back then, and still does today.

I find myself drawn back to my years in high school, when the friends we had seemed to be the ones we’d have forever. Life was just beginning. We never really had an idea how terribly fragile it was, but we would find out in the years to come, very quickly. Watch the faces of the actors in the film and see the innocence, the hope, and with John Milner, the sadness, that all of that must somehow come to an end.

And it does.